play exposes the plight of precarious work: “ABOUT MONEY” AT THE 2022 EDINBURGH FRINGE FESTIVAL.12/8/2022

A new play showing at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival lays bare the impact of insecure work, zero hours contracts and poverty pay on workers who are in the front line of the cost-of-living crisis. Zero Hours Justice is extremely proud to sponsor “About Money”, a play written and performed by 65% Theatre. It tells the story of “Shaun”, an average 18 year old boy who is the sole carer to his 8 year old sister, “Sophie”. Under pressure from his unsympathetic boss at work and trying to find enough money for childcare, he finds himself forced to make decisions that could have devastating consequences. “About Money” presents a very real, powerful and accurate depiction of the daily struggles and dreadful consequences experienced by workers on zero hours contracts. In Scotland there are around 63,000 workers on zero hours contracts, struggling to get by on poverty wages. Our Zero Hours Justice Free Help and Support Service hears every week from zero hours workers unable to buy food, pay their rent or fuel bills or care for their children or elderly relatives due to a lack of shifts or insufficient notice of them. We hope that the play will help highlight our campaign and encourage more businesses to sign up to the Zero Hours Justice Accreditation Scheme, a free scheme which promotes employers who choose to value their workers by not using zero hours contracts.

Following a recent decision by the UK Supreme Court, workers on zero hours contracts could be entitled to more annual leave that what they have previously been getting In Brazel v The Harper Trust (2022), the Supreme Court ruled that hourly-paid employees and workers who work throughout the year, but not necessarily every week, are to be treated as “part-year workers” and so should be entitled to the full holiday entitlement of 5.6 weeks. Previously, many employers of zero hours workers would calculate the holiday entitlement by multiplying the total number of hours worked in the year by 12.07%. That percentage was often used as a rule of thumb because it was the proportion of total holiday entitlement (5.6 weeks) out of the total number of working weeks in the year (52 – 5.6). However, in Brazel, the Supreme Court has said that by using 12.07% of total hours worked, employers were effectively capping the holiday entitlement of those who do not work every work to below 5.6 weeks. Since workers on zero hours contracts are now entitled to 5.6 weeks, even if they do not work every week, the only legitimate method for calculating holiday pay is the Calendar Week method. Each time a zero hours worker requests annual leave, the employer has to work out the average weekly pay over the last 52 weeks, excluding any weeks the worker did not work. If a worker takes a week’s holiday, they should be paid an average week’s pay. The amount of holiday already taken during the holiday year should be deducted from 5.6 to give the outstanding entitlement. It is now unlawful for an employer to roll up accrued holiday pay with your pay in each pay period. But if your employer does happen to do that, and is calculating your entitlement as 12.07%, then it is possible that you are being underpaid if you do not work every week. Obviously, if zero hours worker wants to take part of a week as annual leave, it’s important to understand what constitutes a day. A zero hours worker may not necessarily be working 7-8 hours in per shift – some may work four or five hours, for example, others may work 12 hours, depending on their job. Since “day” is not defined in law, then what constitutes a day’s leave depends very much on the individual context. If a typical shift is for a particular worker is, say, four hours, then one day’s leave would be four hours. It’s important to note that the decision in Brazel does not apply to part-time workers, who are contracted to work fixed hours or days every week, just not five days a week. A part-time worker who works, for example, three days per week, would be entitled to 3x5.6 weeks’ leave (16.8 days or 3/5 of 28 days). Furthermore, the judgement does not apply to those workers who are genuinely casual workers - someone whose casual worker agreement states they are a casual worker, each assignment is a separate contract and a P45 is issued at the end of each assignment. However, Zero Hours Justice is aware, however, that many employers employer casual workers in a way that is far from casual. Whether a casual worker can claim to be a part-year worker depends on the day to day reality and, in particular, whether there was a continued umbrella of employment or an expectation that the employment relationship continued during weeks when there was no work. If you are currently on a zero hours contract and believe that your employer has calculated your holiday pay incorrectly, you may be able to bring a claim for unlawful deduction of wages. You would need to submit the claim to the employment tribunal within three months less a day of the date that the incorrect holiday payment was made. For more information or advice about zero hours contracts, please feel free to call our free national helpline or contact us via our online form.

Following advice and support provided by Zero Hours Justice, a zero hours worker has won her employment tribunal claim against Turner Contemporary for redundancy pay. In January 2021, at the height of the Covid pandemic, the Margate-based art gallery laid off around 40 casual workers following restructuring. Zero Hours Justice was contacted by a number of casual workers, who had worked for Turner Contemporary for a number of years on a regular basis and felt that they should have received redundancy pay. Casual workers, who are supposed to work on an ad hoc basis, do not usually benefit from employment rights such as redundancy pay and protection from unfair dismissal. Some of the casual workers who contacted Zero Hours Justice were able to reach settlements using Acas’ early conciliation service. However, one casual worker, Jan Wheatley (“the claimant”), was so outraged at the treatment by Turner Contemporary (“the respondent”) that she decided to go to court to expose it. She had been working for the art gallery for 10 years when her contract was terminated. The respondent’s casual worker agreement made it clear that work was not guaranteed and workers were not obliged to accept work when offered. However, the employment tribunal found that the wording of the agreement did not reflect the claimant’s day-to-day working reality and that, in practice, she was an employee and so entitled to redundancy pay. Ms Wheatley said: “There is no way I would (or could) have had the confidence and strength to attend a tribunal hearing, without the support and guidance of Zero Hours Justice. “I was advised by ACAS that representing myself would not be wise, and that the respondent's attempts to settle would be seen as conciliatory; I did not have the experience or skills required to present an adequate case and that would put me at risk of having to pay the respondent's legal bill after almost inevitably losing. “Although Zero Hours Justice was unable to provide legal representation, they were more than willing to read over my notes, make suggestions and give valuable feedback and guide me through the legal jargon with expert knowledge and the crucial insight necessary for me to navigate a completely unfamiliar and complicated system. “Zero Hours Justice may be best known for their campaign activity but they were the backbone in my fight, and played a very real, very substantial role in my subsequent win.” It’s important to note that this judgement in Wheatley v Turner Contemporary (2022) turned very much on the specific circumstances of the claimant’s employment. It does not create a general rule for casual workers and redundancy payment. But hopefully, it can show how casual workers and other workers on zero hours contracts may, in reality, be employees and entitled to the associated statutory rights. Some of the key facts that led to the judge deciding that the claimant was an employee were as follows:

The judge also concluded that section 212(3) of the Employment Rights Act 1996 applied to closures of the gallery in-between exhibitions to preserve the claimant’s continuity of service as the closures only led to temporary cessations in work. Once the gallery reopened, the claimant’s was offered work. Turner Contemporary has decided not to appeal the decision. For more information or advice about zero hours contracts, please feel free to call our free national helpline or contact us via our online form.

By Julian Richer, Founder, Zero Hours Justice This article was first published in The Sunday Times on 15 May 2022 as part of a regular weekly column. What was a wealthy capitalist doing giving a speech at Congress House, the TUC’s headquarters in London? The mood was sober. The audience were looking me up and down rather apprehensively. Luckily, I had brought some friends along for moral support. It was January 13, 2020, and I was there to talk about what I saw as a scourge on society. I was firmly on their side. By the end of my nine-minute talk, I felt I had won the audience over — admittedly by trying a little humour, not always easy when discussing a matter of gravity for many. But I was preaching to the converted, after all. I was talking about zero-hours contracts. These ghastly things are occasionally harmless; if a student works a few irregular hours a week in a bar, they are absolutely fine — as long as these people have other income to live on (I am not talking about short-term contracts for pop festivals, summer jobs etc, because here everyone knows where they stand). But it is estimated that a majority of 1 million-odd zero-hours contract workers don’t have that luxury. They are mostly women and have had these contracts imposed on them, or felt forced to sign them when alternative work was not available. This is no different to dockers standing on the quayside waiting for bosses to come along in their trucks to offer them a day’s work if they were lucky. If they weren’t picked, they went hungry. That was 100 years ago — and little has changed. I feel for these people. Research has found that workers on zero-hours contracts are at greater risk of psychological distress and being unhappy than those in full-time jobs. Do we really want stressed, demotivated and disgruntled staff? But they’re lucky to have jobs, aren’t they? What’s all the fuss about? Fine. But try renting a flat when you can’t provide evidence of regular income. Even decent, ethical landlords won’t touch you with a bargepole. The outcome is that some of our hardest-working and most wonderful carers, many of whom don’t even earn the real living wage, literally end up living on the breadline and in debt. Some have to sleep in their cars. Is this the society we want? Where are these workers supposed to live? Social housing stock is like gold dust, with 8 million Britons living in overcrowded, unaffordable and unsuitable conditions (according to the Church of England’s independent housing commission). Another example: a single mum, trying to juggle her busy life and keen to work, arranges childcare. She goes to work but after a couple of hours the boss says: “Sorry, love, it’s quiet today — I’m going to send you home early.” What the hell?! She has earned no money and yet still has childcare costs to pay. This is just not fair. The imbalance of power between bosses and workers is always there. In my opinion, the latter group’s vulnerability is multiplied many times over by zerohours contracts. If bullying or harassment is occurring in a workplace, it is going to be much harder for those not on permanent contracts to speak out about any mistreatment. They just won’t get any hours the next week. Annoyingly, when universal credit recipients are trying to work with the uncertainty of a zero-hours contract, this makes it doubly difficult, with their income changing all the time How come only a quarter of countries in the EU even allow the damn things? They are a great source of poverty and misery. We should be ashamed. So, if you are an employer using zero-hours contracts, please consider binning them. If you are not ready to do that, or your business is a special case and really needs them (such as an events company working only on sporadic dates), please switch to a “fairer hours” contract that gives two weeks’ notice of shifts — with the worker being paid if they are cancelled within that period. I promise this will be to your benefit. Your staff will feel happier and more secure. They will be less stressed, less likely to leave you or not show up for shifts, and be more loyal. Trust me. Postscript: the Daily Telegraph kindly sent along a journalist to cover my speech. Supposedly, this was the first visit by a Telegraph staffer to Congress House in living memory. They dutifully published a piece about my rallying call, with a nice photo of TUC general secretary Frances O’Grady smiling behind me while I was holding forth. I was there to launch the Zero Hours Justice campaign, which I had set up to try and change this abhorrent practice. You can download a PDF copy of the article below:

Without workers’ rights legislation, there will be no effective vehicle for delivering necessary reforms in the workplace, letter warns TUC general secretary Frances O’Grady, Zero Hours Justice founder and business leader Julian Richer and Living Wage Foundation director Katherine Chapman have today (Thursday) written to the prime minister to call for the government to deliver the employment bill in May’s Queen’s Speech. The call comes after reports that the government has now shelved the employment bill, more than two years since the legislation was first promised in December 2019, and following multiple commitments to the bill from ministers. Delivering a boost to workers’ rights “was an urgent task in 2019, when a bill was first announced, and “is even more so today” given the impact of the pandemic, the letter states. The letter warns that “failing to bring forward an employment bill would leave the government without an effective vehicle to make the necessary reforms to the workplace”. In particular, the signatories demand action on the zero-hour contracts when used abusively. The TUC says insecure work has become “endemic” in the UK. The union body estimates that one in nine workers – or 3.6 million people – are in insecure work. This includes more than one million on zero-hours contracts, the great majority of them against their will. The Living Wage Foundation also found that a third (32%) of workers are given less than a week’s notice of their shifts. The letter concludes that “businesses do best when they treat their workers well”, but says this cannot be achieved without an employment bill – urging the government to reconsider its plans. TUC General Secretary Frances O’Grady said: Time and time again, the prime minister said he would boost workers’ rights. Julian Richer, founder of the Zero Hours Justice campaign, said: In my lifetime’s experience of businesses, both large and small, I have found a well-treated workforce is crucial to their success.” Director of the Living Wage Foundation, Katherine Chapman, said: We know low pay is affecting millions during this cost-of-living crisis, but the other side of this coin is insecure work. Million more workers and families are struggling to make ends meet due to a lack of hours, with many faced with uncertain shift patterns provided at short notice. This makes it impossible for people to plan their lives, and often comes with additional costs. The government has given repeated assurances that it would legislate new workplace protections:

ENDS Notes to editors: Letter in full: Dear Prime Minister,

Employment bill We are writing to you as leaders of organisations with a range of perspectives on the world of work to urge you to include an employment bill in the forthcoming Queen’s Speech. Your government came to office with a promise to “protect and enhance” workers’ rights and a manifesto pledge to bring forward “measures that protect those in low-paid work and the gig economy”. This was an urgent task in 2019, when a bill was first announced, and is even more so today given the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on workers, particularly those in insecure forms of work, and on employers. Failing to bring forward an employment bill would leave the government without an effective vehicle to make the necessary reforms to the workplace. Many workers would remain in vulnerable working arrangements. Good businesses would be undercut by those prepared to treat workers poorly. And everyone would be left uncertain about progress of government plans in areas from making flexible working the default to the establishment of a single enforcement body. We are particularly concerned about uses of zero-hours contracts in ways that are abusive.”. For example, the Living Wage Foundation recently found that a third (32%) of workers are given less than a week’s notice of their shifts. This rises to half of those on low wages. Collective agreements between unions and employers, the Zero Hours Justice’s campaign and the Living Hours accreditation programme all have an important role to play in stopping the abusive use of zero-hours contracts. But these need to be underpinned by robust laws that protect the most vulnerable workers by setting a baseline of standards. There remains a strong consensus for reform, reflected in the Low Pay Commission’s proposals on notice periods for shifts and compensation for cancelled shifts. We encourage you to reassess these. The Conservative Party manifesto promised to “make the UK the best place in the world to work”. We are strongly of the view that businesses do best when they treat their workers well. This cannot be achieved without the inclusion of an employment bill in the Queen’s Speech. We urge you to reconsider your plans. Yours sincerely Frances O’Grady, TUC general secretary Katherine Chapman, director of the Living Wage Foundation Julian Richer, Zero Hours Justice founder By Pravin Jeyaraj It is commonly known that the main problem with zero hours contracts is that workers do not know whther they have work from one day or one week to the next. This level of insecurity can result in a great deal of anxiety as people on zero hours contracts, who are often on low incomes too, do not know whether they will be able afford to pay the bills each month. However, one issue that gets significantly less attention is the notice period required to terminate a zero hours contract. The default legal position is that there is no notice period to terminate a zero hours contract. If worker wants to leave straightaway, they can. Similarly, if an employer runs out of work, they can let go zero hours workers straightaway, However, Zero Hours Justice have received numerous enquiries from people who are on contracts that are quite clearly zero hours contracts - no obligation for employer to offer work, no obligation for worker to accept work - but still include a contractual notice period of anywhere from a week to a month. On the one hand, we've heard from zero hours workers who want to leave straightaway or within a week, but are told by their employer that they have serve a month's notice, as per the contract. On the other hand, we have also heard from zero hours workers who have a contractual notice period of a a month, but whose contracts are terminated with less than a week's notice. The employer relies upon the zero hours nature of the contract and ignores the provisions about notice periods, thereby preventing the worker earning income from shifts that had already been agreed. The irony is that workers are still free to turn down work when it is offered and employers have no obligation to offer work, thus rendering a contractual notice period somewhat redundant. It seems that a lot of employers are trying to have their cake and eat it. They want the "flexibility" of a zero hours contract, if it benefits them, but they are not willing to grant the same flexibility to the worker.

By Pravin Jeyaraj

According to new research from the Living Wage Foundation, 32% of workers in full- or part-time employment receive less than a week's notice of any shifts. This rises to 50% for workers earning below the Living Wage. The study, which looked at sample of 2,036 working adults interviewed on 14-15th December 2021, found 57% of UK workers were in jobs involving variable hours or shift work and, of that, 55% said that they were given less than a week's notice of shifts. Even worse, 14% of this group said they did not even receive 24 hours' notice. In addition to not knowing whether one would have work from day to day or from week to week, more than a fifth (21%) have had shifts cancelled at short notice, with the vast majority (88%) not being compensated at their normal rate. So, even if they are given the impression that will have work, it could still be taken away from them. As well as loss of pay, not having enough notice before shifts or shift cancellation was found to result in a an "insecurity premimum":

At the end of the day, being on the National Minimum Wage or the Real Living Wage does not really help if you don't know whether or not you will have the work to get paid. Zero Hours Justice welcomes all attempts to improve the security of work including the Living Wage Foundation's "Living Hours" accreditation: the right to four weeks notice before shifts; guaranteed payment for shifts cancelled within this period; the right to a contract reflecting actual hours worked; and a guaranteed minimum of 16 hours a week. We would prefer that employers stopped using zero hours contracts and other forms of insecure work. But if they really need to use zero hours contracts, our minimum criteria - backed by both the TUC and the CBI - is less onerous than the Living Hours scheme:

The number of people on zero hours contracts once again broken through the one million barrier, according to the latest data from the Office for National Statistics. The data shows that, during the period October to December 2021, 1,030,000 people reported that they were employed on zero hours contracts. This is equivalent to 3.2% of the people in employment. The last time that the number of people on zero hours contracts exceeed one million was for the period April to June 2020, during the first quarter of the pandemic. At that time, the number of reported zero hours contracts was 1,076,000. After that, the number of people on zero hours contracts fell to as low as 879,000 during the third national lockdown (January to March 2021), before rising again. Just as the UK employment rate continues to rise, it is quite clear that Covid only provided a temporary blip in the rise in the use of zero hours contracts. While the number of zero hours contracts has reached its second highest level since records began, the ONS data also shows that the the proportion of people employed on zero hours contracts who say they are working full-time hours has fallen to its lowest level of 30.5%. Conversely, the proportion of zero hours workers who say they are working part-time hours has increased to its highest level of 69.1%. Unfortunately, the decrease in the number of people on zero hours contracts working full-time hours since the first quarter of 2020 has not been reflected in an equivalent increase in the number of people not employed on zero hours contracts and working full-time. At the same time, while the number of people on zero hours contracts working part-time hours has increased to its highest levels, the humber of people not on zero hours contracts who are working part-time hours has actually fallen. These figures suggest that, while the amount of work available to staff on zero hours contracts is decreasing, employers are still offering regular work to zero hours workers without the benefits of permanent employment.

By Pravin Jeyaraj Zero Hours Justice welcomes the decision by London-based Southwark Council to stop using zero hours contracts for its care home staff. Under its new Residential Care Charter, the council has committed to no longer put staff on zero hours contracts in place of permanent contracts, unless individual members of staff specifically ask for it. According to the latest data from the Office of National Statistics, almost a fifth of people employed on zero hours contracts are in the health and social care sector. The data also shows that more than a third (33.7%) of those on zero hours contracts describe themselves as working full-time and, for those who say they are working part-time, the average usual weekly hours is 25.5. This suggests that many employers are using zero hours contracts when the work is fairly regular and could be said to be de facto permanent. In addition to the ban on zero hours contracts, Southwak Council will also pay care home staff at least the London Living Wage (£11.05 per hour), pay them for a proper handover between shifts and provide free training that must be taken during working hours. If you are an employer does do not use zero hours contracts, or you are able to commit to using them in accordance, with our minimum criteria, you are welcome to apply to join our accreditation scheme.

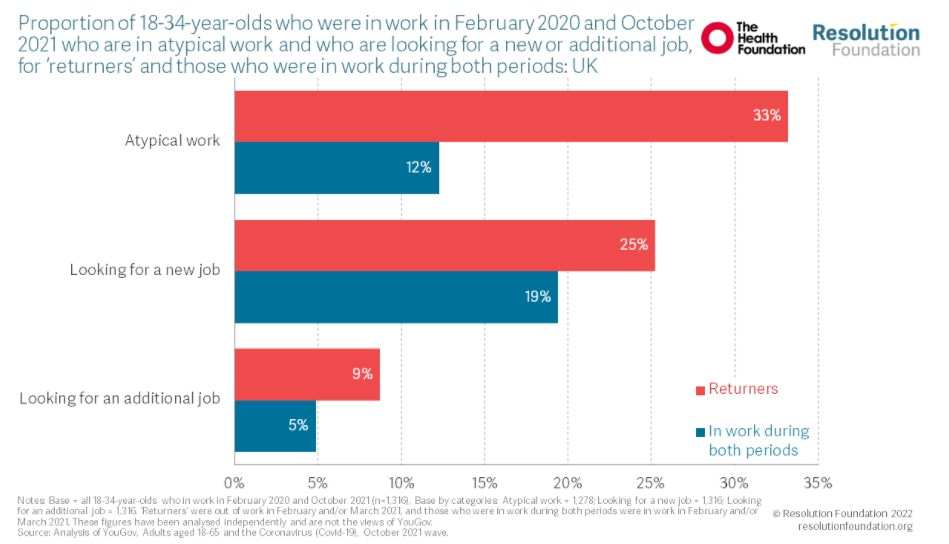

By Pravin Jeyaraj rThe UK employment rate may be rising, although it has not quite reached pre-pandemic levels, but official figures masks a disturbing reality. According to a study by the Resolution Foundation, young people aged 18-34 whose work was interrupted between February 2020 and summer 2021 ("returners") were more likely to in insecure work, compared to those who were able to continue working during this time. In a survey of 6,100 adults, it was found that 33% of young returners were in atypical work (temporary contract, zero hours contract, agency work or variable hours contracts), compared to 12% of those who stayed in work during the pandemic. On top of that, it was also found that 25% of returners were looking for a new job and 9% were looking for an additional job, compared to 19% and 5% of those who could stay in work during the pandemic, suggesting that those who have returned to work are slight less satisfied with their current working conditions. The pandemic also had an impact on how young people felt about working in their sector. A third of young people working in highly affected sectors, such as hospitality, before the pandemic, had changed sectors between February 2020 and October 2021. Only 14 of those working sectors that were less affected by the pandemic decided to switch. Of those who moved out of a highly-affected sector, 30% moved to a different sector and just 3% moved to highly-affected sector. It's incredibly worrying that a lot of young people who were unable to work during the pandemic, through no fault of their own, are finding it difficult to find secure work. This will have had an impact on their earnings and could worsen both the cost of living crisis and their ability to plan for the future. It is also clear, from the study, that young people do not want to have insecure work and taking the opportunity to switch to sectors that can offer more secure work.

|

contactFor press enquiries or permission to reuse content, please contact: Archives

June 2024

CATEGORIES

All

|

||||||||

|

Company No: 12417909 Registered Office: 38 Coney Street, York, Y01 9ND

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed